Make Your Climbing ROCK Solid!

Rock Climbing

Rock climbing has gained popularity over the years as indoor rock climbing gyms started to pop up and accessibility increased. The sport is expected to grow after its debut in the Tokyo Olympics. There are four forms of rock climbing done outdoors or indoors: traditional, sport, speed, and bouldering (2). Firstly, traditional climbing (or trad) is a partner climb involving removable equipment anchored into cracks in the wall by the first climber,

and cleaned up by the second climber as they both make their way up a route. Secondly, sport climbing is another partner climb, but it relies instead on permanent anchors in the rock. Both trad and sport climbing are done via a top rope. The rope is looped around a pulley mechanism at the top of the climbing route, or via lead climbing where the climber pulls the rope up as they climb. Thirdly, speed climbing is done indoors in a competition setting where two climbers race to the top. Lastly, in bouldering, climbers tackle problems which are done lower to the ground without a rope. In the Tokyo Olympics, climbers will compete in three disciplines – speed, bouldering, and lead (most similar to sport climbing). Without question, each type of climb requires adequate strength, power, endurance, flexibility and skill.

Rope or No Rope

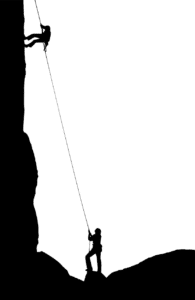

Most types of climbs utilize the safety of a rope and harness. In partner climbs, there is a climber and a belayer, both attached to the same rope. One person climbs (climber) and advances up the rock face or wall, while the other (belayer) stays anchored and uses tension in the rope to catch the climber in case of a fall. With the added safety of the rope, climbers can attempt more difficult moves.

Common Rock Climbing Injuries

Upper Extremity

As with any sport, one is susceptible to injury. The most common rock climbing injuries are overuse injuries of the upper extremity (1, 6). Sixty percent at the hand/wrist and 40% at the shoulder/elbow; of the hand/wrist injuries, 52% involve the finger tendons (1). Each finger has pulleys which help keep the flexor tendons in place when the fingers flex and extend (bend and straighten). A pulley injury is graded on a I-IV scale with IV being the most severe. Typically a climber may hear or feel a pop, followed by the finger giving way and pain. It is most common in the ring and middle fingers (1). Fortunately, most pulley injuries can be treated conservatively without surgery (1).

The shoulder is the second most common injury site in the climber (1). This can occur through overuse or trauma if a climber falls. In addition, elbow injuries are due to overuse and are commonly located near the medial epicondyle (inside elbow) (1, 2).

Lower Extremity

Lower extremity injuries mostly occur as a result of falling from height, some resulting in a fracture (2). Unique to rock climbing, a concentric hamstring injury can occur from using the heel hook technique (4). Additionally, rock climbing shoes are attributed to foot pathologies (2).

Also worth mentioning are head and spine injuries, although they aren’t as common. Some climbers may exhibit the “climber’s back,” a posture that consists of a forward head, rounded upper back, forward shoulders, and an increased low back curve. This may simply be a pain-free adaptation to the sport, with climbing ability level highly correlated to postural changes in experienced climbers (5). In some cases, this can lead to spondylolysis, chronic back pain, and thoracic outlet syndrome (2).

Rock Climbing Injury Prevention

Knowing the mechanism and location of common climbing related injuries can help guide strategies for injury prevention. Most injuries are due to overuse, therefore having adequate strength and endurance to climb is key. Appropriate dosing is important when strength training; if the resistance or load is too low, the climber may not be strengthening to the capacity needed to perform a climb.

Fatigue of finger and elbow flexors occur before shoulder fatigue sets in, so building adequate strength in these regions is key, not only for performance, but for injury prevention (3). Fingerboard training helps strengthen the fingers using different loads and different grips. When training off the wall, consider the different directions of force applied to the body while on the wall. For example, targeting a muscle called the brachialis will strengthen elbow flexion in a pronated position (palm facing the wall, pulling up), while targeting the brachioradialis will strengthen elbow flexion in a neutral position (side pull, reaching out to the side and pulling in). Compound movements that mimic the demands of the sport strengthen the upper extremity. Climbing performance correlates with pull ups, bent arm hang time, and single arm pulling strength (3).

As a belayer, neck strain may occur due to constant cervical extension (looking up) as you spot your climbing partner. One can use climbing glasses to avoid looking up. If pain is associated with the “climber’s back” posture, strength and mobility work in the opposite directions will help reduce postural stresses.

Find a Physical Therapist!

Regardless of where your injury may be, finding a physical therapist who has the knowledge of different climbing positions, climbing mechanics, and strength required to climb will help create a tailored training program. Fortunately, many climbing related injuries are treated conservatively with a good training program from a physical therapist. In conclusion, if you’re a rock climber experiencing pain from a climbing injury, the Agile staff is here to help you feel better sooner than later. Sixty-eight percent of Agile PTs have board certifications versus the national average of 12.5%, giving Agile the uniquely qualified edge to get you back to rock climbing as soon and as safely as possible!

About the Author: Sarah Jay, PT, DPT:

Sarah completed her Doctorate of Physical Therapy from Howard University in 2014 and graduated from UC Irvine in 2009 with a bachelors in Public Health. She has worked in the physical therapy field since 2008 where she started as a physical therapist aide and found her calling. Sarah believes that rehab is a team effort and encourages her patients to be active in their recovery process by creating individualized and innovative treatment plans that meet the patient’s goals. She has experience working with a variety of patients from the grandparent who wants to play with their grandchildren to the athlete who wants to complete an ultra marathon. Sarah is excited to get her patients moving and doing what they love. In addition, when not treating patients, Sarah enjoys rock climbing, hiking, photography, traveling, and food.

References:

- Chang, C. Y., Torriani, M., & Huang, A. J. (2016). Rock Climbing Injuries: Acute and Chronic Repetitive Trauma. Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology, 45(3), 205–214. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2015.07.003

- Cole, K. P., Uhl, R. L., & Rosenbaum, A. J. (2020). Comprehensive Review of Rock Climbing Injuries. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 28(12), e501–e509. doi:10.5435/jaaos-d-19-00575

- Deyhle, M. R., Hsu, H.-S., Fairfield, T. J., Cadez-Schmidt, T. L., Gurney, B. A., & Mermier, C. M. (2015). Relative Importance of Four Muscle Groups for Indoor Rock Climbing Performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(7), 2006–2014. doi:10.1519/jsc.0000000000000823

- Ehiogu, U. D., Stephens, G., Jones, G., & Schöffl, V. (2020). Acute Hamstring Muscle Tears in Climbers-Current Rehabilitation Concepts. Wilderness & environmental medicine, 31(4), 441–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wem.2020.07.002

- Förster, R., Penka, G., Bösl, T., & Schöffl, V. (2008). Climber’s Back – Form and Mobility of the Thoracolumbar Spine Leading to Postural Adaptations in Male High Ability Rock Climbers. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 30(01), 53–59. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1038762

- Lum, Z. C., & Park, L. (2019). Rock climbing injuries and time to return to sport in the recreational climber. Journal of Orthopaedics. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2019.04.001